Way back in the early parts of this series (parts 11, 12, and 14 touch on this issue) I looked at this. I thought it might be worth a fresh look.

I would like to mention, first, that I think there is a bit of false American exceptionalism here. Usually, I see this when someone cynically paints public homeownership policies as an unwise attempt to force the public into an unsustainable version of a uniquely American dream. But, according to this Wikipedia article, American homeownership rates are actually pretty low compared to most other countries. The choice of public policies in this area is a subtle and complicated one, and I would be as happy to see some changes as anyone, but I don't think there is anything particularly American about public or private tendencies to celebrate homeownership.

Here is a graph of homeownership rates, from the SCF, by income quintile (the top quintile is separated into 2 deciles). What I have pointed out previously is that essentially all of the increase in homeownership during the boom years was among the top 60% of incomes. There isn't any evidence from the SCF of a surge in low income home buyers.

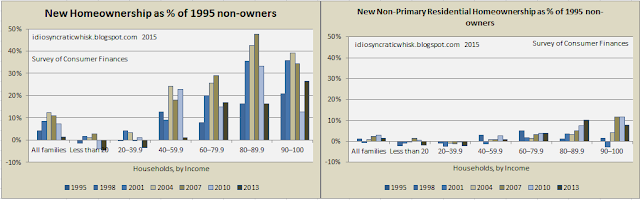

Here is a graph of homeownership rates, from the SCF, by income quintile (the top quintile is separated into 2 deciles). What I have pointed out previously is that essentially all of the increase in homeownership during the boom years was among the top 60% of incomes. There isn't any evidence from the SCF of a surge in low income home buyers.The next pair of graphs show the change, from 1995 to 2013, in homeownership rates within each income group. The left graph is for primary residence and the right graph is for non-primary residence.

Since homeownership among the highest income households is already very high, when homeownership rises, we might expect most of the new ownership to happen at lower incomes. For example, if 100% of the top 40% of households already were owners, then even if marginal new owners were the highest income non-owners, the average new homeowner would have a lower income after the rise in ownership than they had before, even without any downward bias. Now, it happens that this wasn't the case. As I outlined in those earlier posts, the income of the average homeowner actually increased during the boom, even with this natural force that should bias the average down as homeownership rises.

In the next pair of graphs, I try to account for this by looking at a new measure. In this pair of graphs, I measure the change in homeownership in each income quintile over time, as a percentage of the non-owners in 1995. This doesn't change the accounting for the bottom 40% much, because there just wasn't much net aggregate home buying among those households. The bust has dropped homeownership among those households. This has been strongest among the lowest quintile. I suspect that since homeownership in that quintile appears to be concentrated among retired households with low leverage, much of this drop is the result of households dealing with unemployment, etc., losing their homes, and falling from higher quintiles as a result of the recession.

Among the middle quintile, at the peak, about 20% of the previous non-owners had become owners during the boom. This has reversed in the bust so that net homeownership in this quintile is back at 1995 levels.

Among the top two quintiles about 30% to 45% of non-owners had become owners by the peak. This has fallen since then, but in 2013 about 15% to 25% of previous non-owners still were owners.

During the boom, homeownership rose and was slightly skewed toward higher income households, relative to the existing pool of homeowners. During the bust, homeownership has fallen and has become significantly more skewed toward higher income households.

One response I have seen to findings that subprime loans weren't particularly related to a decline in buyer incomes is that many of them were made to higher income households who were engaged in speculation. Interestingly, ownership of non-primary residential real estate did rise among the top quintile, but it has generally remained elevated since the bust. Now, it could be that there has been a transition between high income households that defaulted on non-primary real estate holdings during the bust and opportunistic high income households who have entered the market since then to buy up cheap foreclosures. So, maybe this group of owners still accounts for some of the defaults. But, I think it is interesting that we don't see much sign of distress among this group in this data.

MSA Data on Homeownership

Can cities shine any light on this?

Here is a scatterplot comparing homeownership rates and Price/Income levels, by city. (The data I am using has a discontinuity in 2005. This is why my charts don't cross that period. Before that year some of the MSA boundaries are less inclusive, which tends to bring down ownership rates and drive up P/I levels because the urban cores are a larger portion of those MSA's before 2005. This affects the levels, but it shouldn't affect the trends that much.)

This first pair of graphs shows the movement up in P/I and in homeownership rates from 1995 to 2004, then the move down in both measures since then. It's hard to learn much from these graphs about the boom, though. But, it is clear that in all scenarios, high homeownership is strongly correlated with lower price levels.

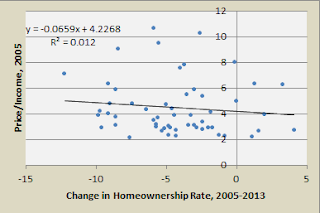

In the next pair of graphs (for the 1995-2004 boom period and the 2005-2013 bust period) I compare the change in the Homeownership rate for a city to the Price/Income level of the median home in that city at the end of the period. There is no relationship. If anything, homeownership increased the most in the cities with the lowest prices. In the next graph, below, comparing the subsequent change in homeownership to the beginning Price/Income level in 2005, the slope of the regression line is a little steeper. This is because there were a few cities that did see sharp price swings toward the end of the boom, which subsequently saw sharp drops in prices and homeownership - cities in Florida, Arizona, Nevada, and inland California. These were generally cities with low to moderate home prices that spiked toward the end of the boom.

In the next pair of graphs, I compare the change in the Homeownership rate for a city to the change in the Price/Income level of the median home in that city over each period. In the boom period, there is no relationship. Most cities did not see an extreme rise in Price/Income, and the few that did see an extreme rise in Price/Income did not exhibit a systematic trend in homeownership rates. Homeownership, at the MSA level, appears to have had nothing to do with the price boom.

In the bust period, we do see some relationship between changing homeownership rates and changing home prices. In MSAs with falling prices, we also tend to see falling homeownership rates. For a 1% fall in an MSAs homeownership rate, relative to other MSAs, since 2005, we see a fall in Price/Income of about .05. Even though the relationship is weak and is not statistically significant, the effect is fairly strong. Most cities have P/I around 3, so a relative drop of 0.5 in the Price/Income measure for a city with a 10% drop in homeownership compared to a city with no drop is dramatic.

But, the takeaway here is that none of these relationships between cities is statistically significant and to the extent there is any relationship at the inter-city or national aggregate level, it was a bust effect, not a boom effect. On the margin, this has mostly been a story of high income households buying homes in low priced cities. The shift of households into ownership was not related to the rise in home prices in the boom. But, the subsequent collapse of mortgage credit and housing markets did push some households out of their homes. This corroborates research that has shown that mortgage defaults were strongly related to loss of equity. These losses were concentrated in secondary cities that tended to be destinations for households moving from the Closed Access cities. On net, though, what the entire process has led to is Closed Access cities which continue to be very costly, secondary cities that were whipsawed through a boom and a bust, and the majority of the country that never had much of a boom, but has had to endure a decade of curtailed housing starts and mortgage credit. In this last graph, we can see the endurance of the high cost of a few supply-constrained cities and the relatively normal behavior of most of the others. These scatterplots compare the median home price in each city from 2005 or 2013 to 1995. The difference between cities has steepened. The cities that had P/I ratios below about 2.5 in 1995 are now likely to have lower P/I ratios than they did then, despite very low interest rates. Those cities didn't need a correction even though some of them built a lot of homes and saw significant increases in homeownership.

But, the takeaway here is that none of these relationships between cities is statistically significant and to the extent there is any relationship at the inter-city or national aggregate level, it was a bust effect, not a boom effect. On the margin, this has mostly been a story of high income households buying homes in low priced cities. The shift of households into ownership was not related to the rise in home prices in the boom. But, the subsequent collapse of mortgage credit and housing markets did push some households out of their homes. This corroborates research that has shown that mortgage defaults were strongly related to loss of equity. These losses were concentrated in secondary cities that tended to be destinations for households moving from the Closed Access cities. On net, though, what the entire process has led to is Closed Access cities which continue to be very costly, secondary cities that were whipsawed through a boom and a bust, and the majority of the country that never had much of a boom, but has had to endure a decade of curtailed housing starts and mortgage credit. In this last graph, we can see the endurance of the high cost of a few supply-constrained cities and the relatively normal behavior of most of the others. These scatterplots compare the median home price in each city from 2005 or 2013 to 1995. The difference between cities has steepened. The cities that had P/I ratios below about 2.5 in 1995 are now likely to have lower P/I ratios than they did then, despite very low interest rates. Those cities didn't need a correction even though some of them built a lot of homes and saw significant increases in homeownership.

Excellent. That is exactly what happened in Las Vegas. Outside buyers bought in the boom. It was speculation, primarily. However, some Hispanic buyers, and I don't know how you could measure it, were put into loans that they could never pay back and it appears they were not informed as to the terms. But central California, parts of Florida, and Las Vegas housing prices were bumped up by speculative demand.

ReplyDeleteNice post. Print more money, build more houses....highest and best use universally!

ReplyDeleteBen, you never gave me a link to the idea of placing bonds with social security. And how do we print more money when there is a shortage of bonds? Sumner says there is a shortage of money, and I certainly agree that is the case on main street. But there is a shortage of bonds. What will the Fed take as collateral, sticks, or recycled newspaper? Lol.

DeleteGary--it is my own idea.

ReplyDeleteAs for a shortage of bonds, the Japanese government has been creating many. In the unlikely event there are no more Treasury bonds to be purchased, then go ahead and purchase Japanese gilts.